资料中心消耗的能量多数最终以热的形式散失;在某些专用设施中,冷却用电可占总用电超过 30%。这些原本被浪费的低品位热,通常约为 25°C(原文同时标示 77°F),而采用液冷的新型中心可达 30–40°C,恰好可用来驱动水源热泵并服务多种终端用途。例子包括 Deep Green:其在 2023 年于英国 Devon 以小型资料设施为公共泳池供热,并规划在 Bradford 建置 5.6 MW 设施接入可为约 10,000 户家庭供暖的区域热网,以及在美国 Michigan 州 Lansing 建置 24 MW 中心以加热市中心多数区域;使用者支付热泵运转费,但 Deep Green 免费提供热源,让热泵效率更高并降低能源帐单。

这类热回收并非新概念:Mark Lee 指出北欧数十年来已擅长此道,例如 Meta Platforms Inc. 位于丹麦 Odense 的资料中心可为 6,900 户家庭供暖,部分原因在于当地已建成较完善的热网。工业端也有案例:挪威资料中心公司 Green Mountain AS 与鱼类及龙虾养殖场合作利用余热;龙虾最佳生长温度约 20°C,透过资料中心冷却系统的峡湾海水,成熟时间可缩短至约 18 个月,而非 5 年。政策正逐步跟上:英国可把 AI 成长区与 2035 年前使热网供热量「超过倍增」的目标结合;欧盟要求容量超过 1 MW 的资料中心在可行时必须回收利用其热;德国更进一步规定必须回收最低占比,且该门槛将在 2028 年 7 月提高到 20%。挑战在于热需求端与资料中心选址必须靠近以降低传输损失,但大型新案常因电网限制而外移至 London 的 M25 之外;Asad Kwaja(AECOM)强调协调可行但需要「非常早期的规划」,而更便宜、去碳化的供暖也能降低社区阻力。

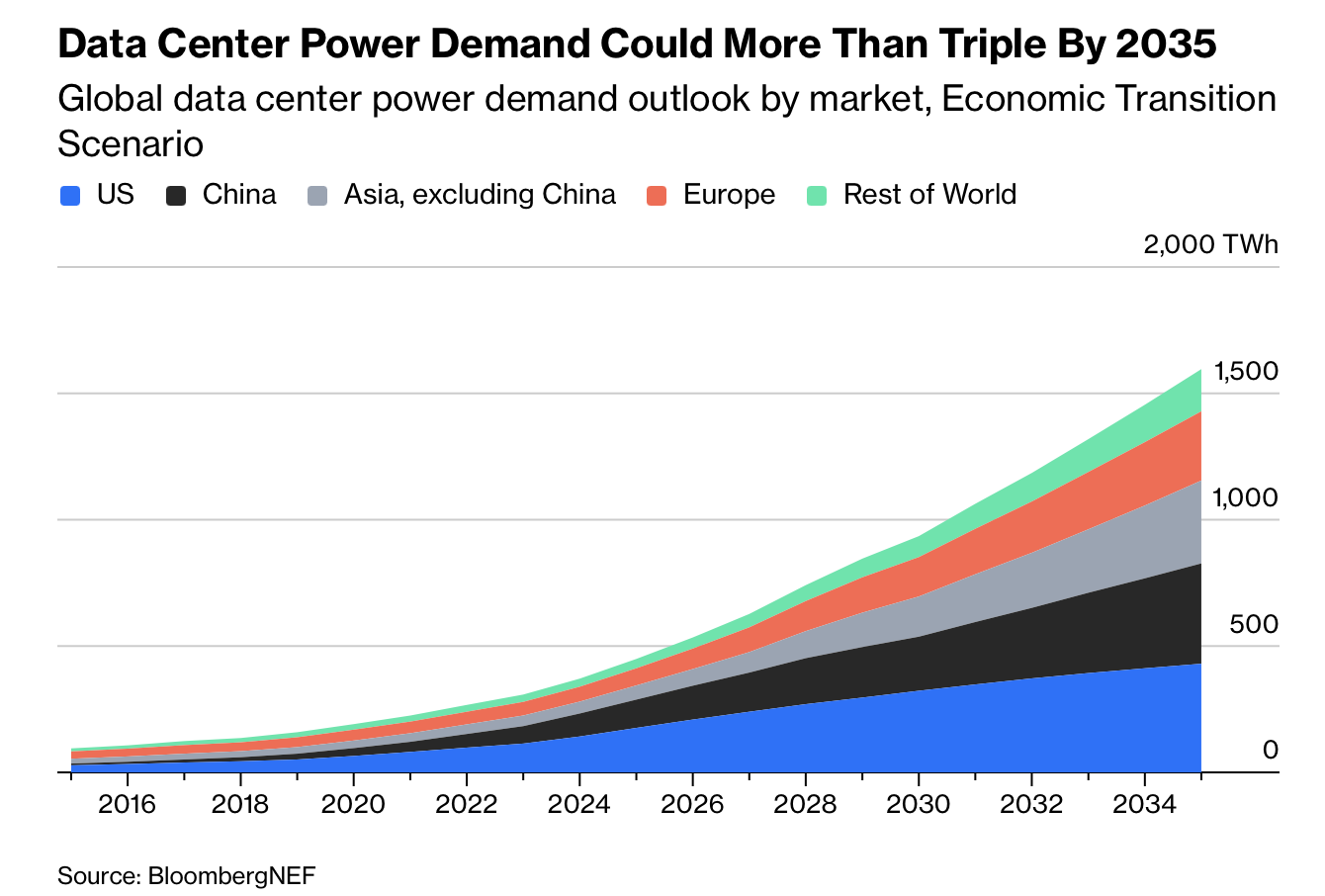

By 2030, global data-center buildout could reach as much as $7 trillion (US$7 trillion), and the roughly 12,000 facilities already operating worldwide underpin cloud storage of about 200 zettabytes (roughly the equivalent of 1 trillion hours of high-definition cat videos). Even as computing becomes more efficient, generative AI and other workloads keep pushing demand upward, putting unprecedented strain on electricity grids and water supplies. The question is therefore not only how to add capacity, but how to make data centers return value to the systems they draw from.

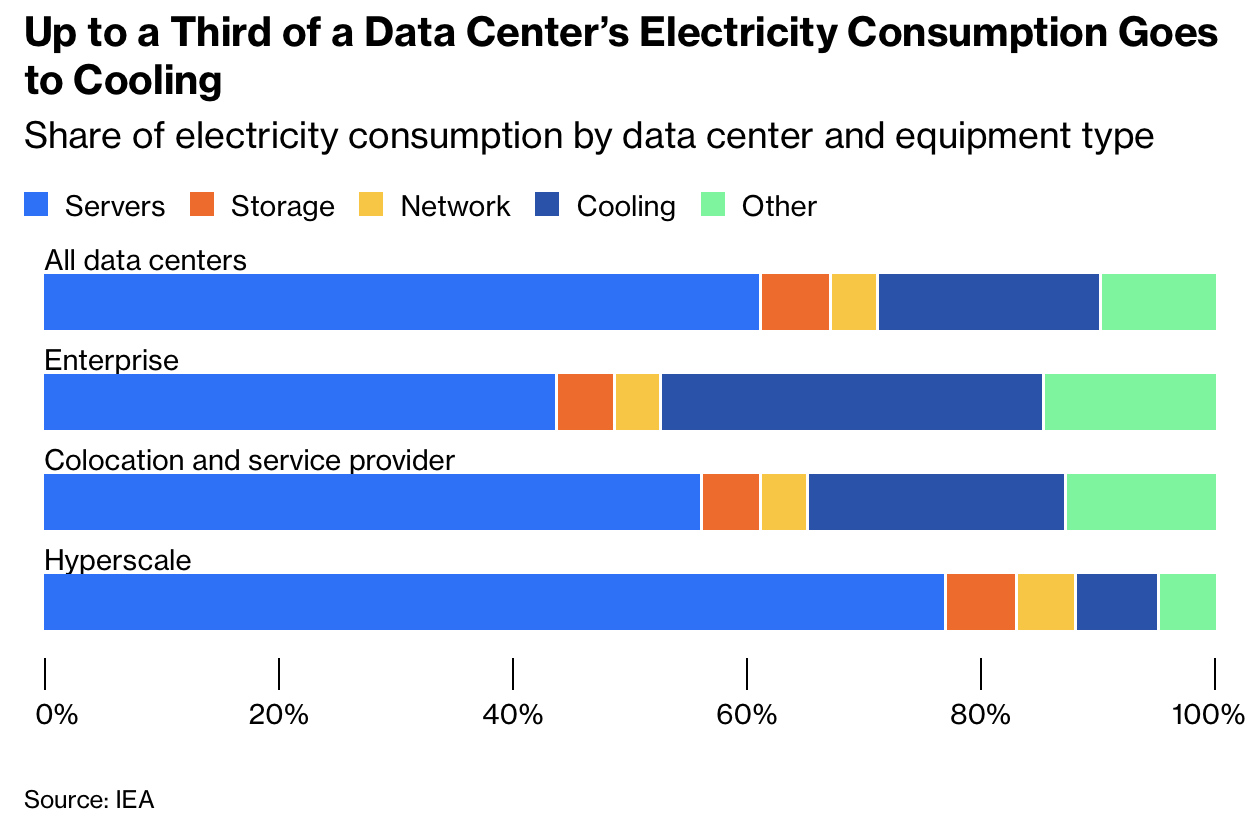

Most of the energy data centers consume ends up as heat, and in some dedicated facilities cooling can account for over 30% of power use. This low-grade heat is typically around 25°C (also given as 77°F in the original) and, in newer liquid-cooled centers, can reach 30–40°C, which is well suited to priming water-source heat pumps for many end uses. In 2023, Deep Green used a small data facility to heat a public swimming pool in Devon, England, and it now plans a 5.6 MW site in Bradford connected to a heat district equivalent to warming 10,000 homes, plus a 24 MW center in Lansing, Michigan intended to heat much of downtown. Users pay to run the heat pumps, but Deep Green supplies the heat for free, raising pump efficiency and reducing energy bills.

Heat reuse is not new: Mark Lee notes that Nordic countries have done it for decades, and Meta Platforms Inc.’s data center in Odense, Denmark, warms 6,900 homes, aided by mature heat-network infrastructure. Industrial cases exist too: fish and lobster farms have partnered with Norway’s Green Mountain AS to use waste heat, with lobsters growing best at about 20°C and reaching eating size in roughly 18 months rather than five years when fjord seawater from the cooling system is used. Policy is beginning to catch up: the UK could pair AI growth zones with a goal of more than doubling heat supplied by heat networks by 2035; the European Union requires data centers above 1 MW to reuse heat if feasible; and Germany mandates a minimum reuse share that will rise to 20% by July 2028. The hard part is siting—heat must be close to demand to limit losses, yet grid constraints push large projects outside London’s M25—so Asad Kwaja of AECOM argues coordination is possible only with very early planning, while cheaper, decarbonized heating can also reduce local resistance.