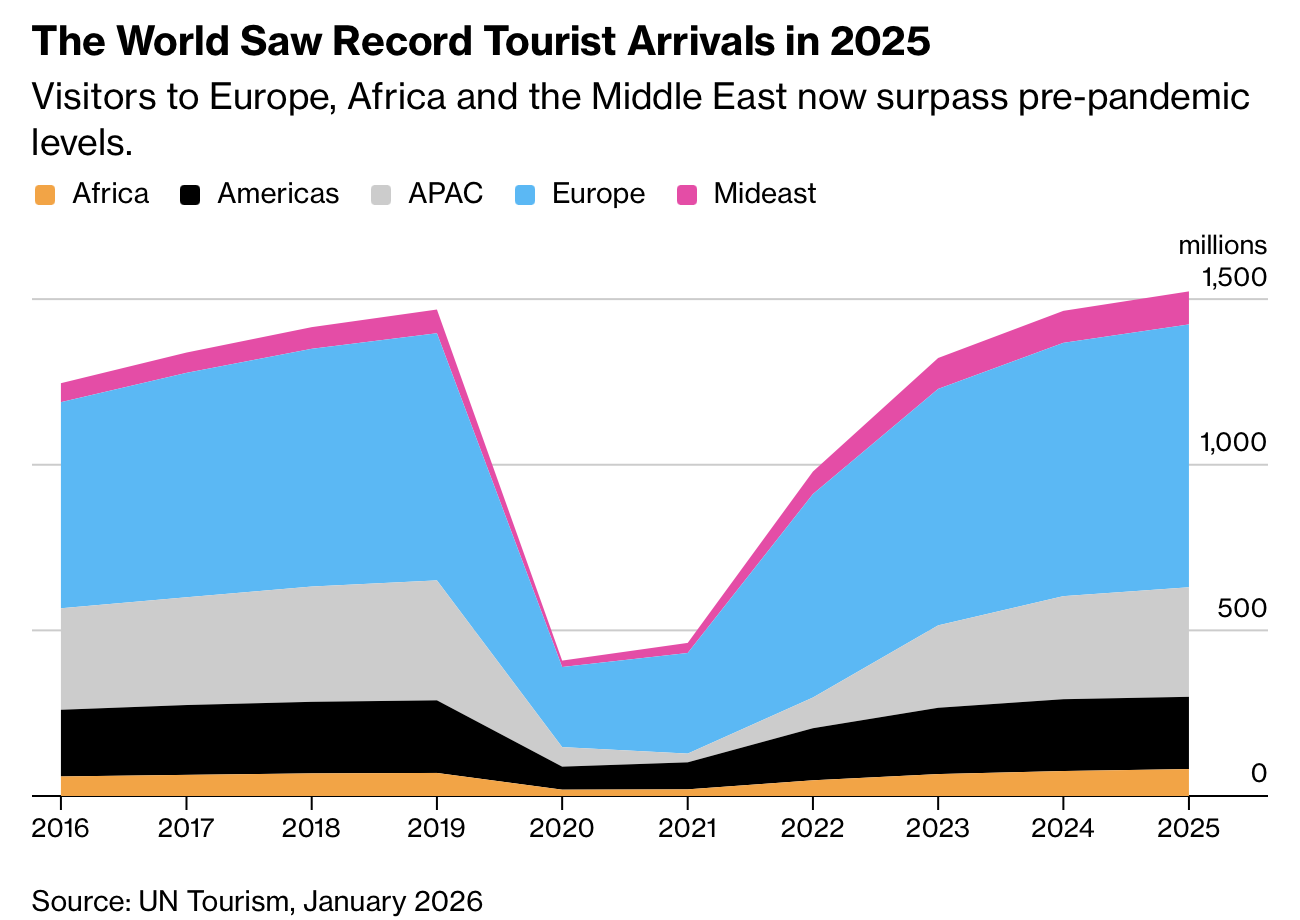

全球旅游业在2025年达到历史高位,国际游客人数达15.2亿,比2019年疫情前峰值高出近4%,其中超过一半流向欧洲。旅游需求的集中使巴黎、罗马、巴塞罗那等城市承压加剧,也促使地方开始通过价格与准入机制分担成本,例如巴黎部分咖啡馆向游客加价最高50%。专家认为,这并非“宰客”,而是应对过度旅游的潜在工具之一。

过度旅游的核心并非单纯的人数,而是局部高度集中与收益分配失衡。社交媒体与廉价住宿平台推动游客涌入原本以本地生活为主的空间,改变商业结构与居住体验。实例显示,波尔图的莱罗书店年接待约120万人,2015年购书者不足10%;巴黎莎士比亚书店日访客从约30人增至2,000至3,000人。尽管门票或限流(如€10入场费)可改善收入与秩序,但对拥挤本身的缓解有限,且可能因“稀缺信号”反而强化需求。

政策工具的有效性取决于精准性与公平性。限制邮轮靠港、设定日客流上限(如杜布罗夫尼克将邮轮限制为每日2艘、少于5,000人)被证明有效,但无城墙城市更难执行。提高飞行成本可能误伤低频旅客,因为全球50%的航班由1%的人群完成。更具共识的方案包括居民优惠、技术分流与收益在地化。当前仅有2%至4%的人口每年进行国际飞行,但一旦过度旅游固化,逆转极难,或需更高成本与更严格管控。

Global tourism reached a record in 2025 with 1.52 billion international arrivals, nearly 4% above the 2019 pre-pandemic peak, and more than half of visitors went to Europe. Concentrated demand has intensified pressure on cities such as Paris, Rome and Barcelona, prompting local measures to redistribute costs, including charging tourists up to 50% more in some Paris cafés. Experts argue such pricing is less a rip-off than a potential tool to manage overtourism.

The core problem is not sheer numbers but extreme concentration and uneven local benefits. Social media and cheap accommodation platforms funnel visitors into formerly local spaces, reshaping commerce and housing. Examples show scale effects: Porto’s Livraria Lello receives about 1.2 million visitors annually, with under 10% buying books in 2015; Paris’s Shakespeare and Company rose from roughly 30 daily visitors to 2,000–3,000. Entry fees or caps (such as a €10 ticket) can improve revenue and order, but they do not reliably reduce crowding and may even intensify demand by signaling scarcity.

Policy effectiveness hinges on precision and fairness. Limiting cruise calls and daily caps (Dubrovnik restricts arrivals to two ships and under 5,000 visitors a day) has worked, but wall-less cities face tougher enforcement. Raising airfares risks penalizing infrequent travelers, since 50% of flights are taken by 1% of the population. More consensus-backed options include resident discounts, technology-enabled dispersion, and local value capture. With only 2%–4% of people flying internationally each year, once overtourism takes root it is hard to reverse, often requiring higher costs and stricter controls.